-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 1

use_git

This is only a collection of the most important tasks you will need. For more information see the excellent Git Pro Book by Scott Chacon. The official git website.

The traditional way to work with Git repositories is to use bash / command line prompts. This allows you to do all the necessary steps like (1) pulling the recent copy of a remote repository to your local computer, (2) staging changed files to be commited to the repository, (3) commiting files to the repository (http://git-scm.com/book) and (4) pushing the changed repository back to the remote host.

If you want to see, if your repository was changed since the last pull, or if some data are already staged for commit, you can type

git status

This assumes that you have a working SSH connection to the remote git repository, e.g. the workstation. If you want to pull (in subversion this was called 'check out') from a remote repository, e.g. on the workstation or on GitHub, you need to type

git pull <origin> master

Here, you need to specify from which remote server you want to pull. Your repository holds a list of known servers for this particular repository. You can see this list if you type

git remote

This returns you a list of names that are valid for the use in <origin>. A repository cloned (see below) from somewhere stores the location of it's parent under the name origin. So in that case (i.e. most cases) you probably need to write

git pull origin master

Sometimes you need to set or rename the remote clone of your repository. This works via

git remote <name> git@kefi118:~repos/nameofrepository.git

which enables you to pull from that repository afterwards:

git pull <name> master

After a successful pull you will have an exact match of the files in branch 'master' that are stored on the remote repository in your local repository. Read more about branches below.

The purpose of staging is to make a clean selection of the changes that are tracked at the next commit to your repository. This allows you to avoid cluttering your version history. it also allows you to separate changes made in a particular part of the project, e.g. the manuscript, from the changes in another part, e.g. computer code. Staging generally happens with git add.

git add filename.r

or

git add folder

Running a git status afterwards will show you that this file/folder is listed for the next commit. However, usually you do not want to add only one file.

Staging entire folders or all files: Before you try that, you should ensure that there is a .gitignore file specified in your git repository. This file excludes files from automated adding to the next file commit. Otherwise you will add files which are not supposed for version control, e.g. auxiliary files from LaTeX or created pdfs or huge data files.

Best first to preview which files are going to be staged with option -n:

git add -n .

If you are happy with this file list, you can stage:

git add .

So once you are happy with the files staged, you can commit.

git commit -m "<add message here>"

This is adding an object to your git repository, which can be identified by an absolutely unique name, the SHA-1 hash. It might look something like 803ea39a0feed898027bd84dd5bcdfb11f781893. This object contains the name of the previous commit, a time stamp and the message you added, as well as all the changes you made compared to the previous commit.

Those changes are now saved and tracked in your local repository.

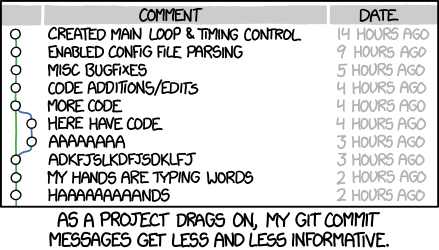

Messages are obligatory in git. If running git from command line, the easiest way to add comments is specify the parameter -m. If you don't do it, an editor window will pop up and ask you to enter a message. It is very important to choose a concise and descriptive message, because it will allow you to quickly find that one commit where you did change that particular thing.

So, don't become lazy on messages:

You might want to share your recent commits with a remote repository, e.g. on the workstation or on GitHub. Remember from earlier (pulling), that your local repository knows the location of it's own remote clones. git remote -v will show you all of those.

To push your local changes to the one called origin, simply do

git push origin master

That's all you need for the everyday workflow.

First of all, there are different ways how you can obtain a repository on your local computer: Cloning an existing repository (somewhere online or elsewhere on your computer) or creating a new repository.

After installing git (see below), you are able to spawn git repositories wherever you like. Create a folder and initialise.

cd path/to/your/projects/

mkdir newrepository.git

cd newrepository.git

git init

After that you might want to backup your repository or share it with somebody via a remote server. You need to initialise an empty repository on a remote server and specify it as a remote for your own repository. So, first, go to the remote computer and create the remote repository as bare directory.

cd ~/repos/

git init --bare name_of_repository.git

To do that on our workstation, you need to log-in to the user git via ssh. So passwordless ssh access to the workstation needs to be configured for your computer.

Then, in your local repository, set a new remote called workstation

git remote -v

git remote add workstation git@kefi118:~/repos/repository.git

If you want to get a copy of an existing repository from somewhere else you need to clone it.

cd path/to/your/projects/

git clone git@server:~/repos/repository.git

This also initialises the origin of this repository for convenient pull and push (see above). In case of the repository labdocs.git on our workstation this would be

git clone [email protected]:~/repos/labdocs.git

Each repository keeps a list of the known remotes, i.e. copies of this repository on other computer. you can call them

git remote -v

The default name of the parent copy, from where and to where you pull and push updates, is simply origin. But it can be renamed to a more meaningful name, e.g. workstation

git remote rename origin workstation

Branching, or forking, is a very powerful tool in version control that lets you work on different development paths, for example to try out things without crashing the working version. After a successful implementation, you would remerge the branch with the master version.

Forking is basically the same thing, but without the intention of merging the development paths back together.

look up:

git checkout

With certainty you will have milestones in the project. Even if you might not call them 'milestones', there are points in time during the project which are important to remember. Such milestones might be quite obvious, like

- the submission of a manuscript

- the start of an intensive simulation run

but they also might be less important or obvious, but still important to have a permanent reference.

- handing out the manuscript to somebody else for pre-review

- handing out the code for review

- having finished work on an important element of your simulations (e.g. a function)

In those cases you might want to add a tag to your project. This is a lable that is easy to find again. A reference in project-time. See a list of the existing tags on the project with

git tag

For all the cases mentioned above, it is best to use annotated tags, which are able to restore the recent content of the project and contain additional information. You can save a tag by typing

git tag -a v0.2 -m "second internal review"

However, like branches (see below), tags are not pushed to or pulled from a remote by default. This means, if you want to share the tag, you need to push it to the remote repository, e.g. by typing

git push origin v0.2

If you want to restore somebody elses tag, you need to pull it first.

git pull origin v0.2

Be aware, that now your working directory will show the state of the repository that was tagged. Of course, all later work is still there. You can switch the view of your working directory any time back to master by using

git checkout master

For me as a beginner, GitHub.com was probably the best way to get in touch with git's system of version control. GitHub is a hosting service that is free for private use. It provides you with an own git repository on their servers, which also means that the files are always savely stored in some immortal cloud storage. This of course means, that you have to register some personal data and leave your files with a US company. In terms of privacy, it does not matter too much in this case, since GitHub does not keep files private (unless you pay for it). Since GitHub is supporting open source development all files stored on it are freely accessible to anyone. If you use GitHub for free, you have to agree with that. GitHub does not make money out of adds or other dirty buisness with the data they keep for you. It makes its living only from hosting closed source developers and companies.

Once logged in, you can set-up and clone repositories online. Follow the tutorials. Its quite easy. You can start right away and create content online, via the build-in editor. The GitHub for Windows tool allows a quite easy integration in your everyday work.

Visit the web page and set up an account. It only needs a username, a valid e-mail adress and a password. After the log-in you are guided through the first steps. There are plenty of video tutorials and manuals.

Biodicée Docs by Sonia Kéfi & Vincent Devictor et al. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.